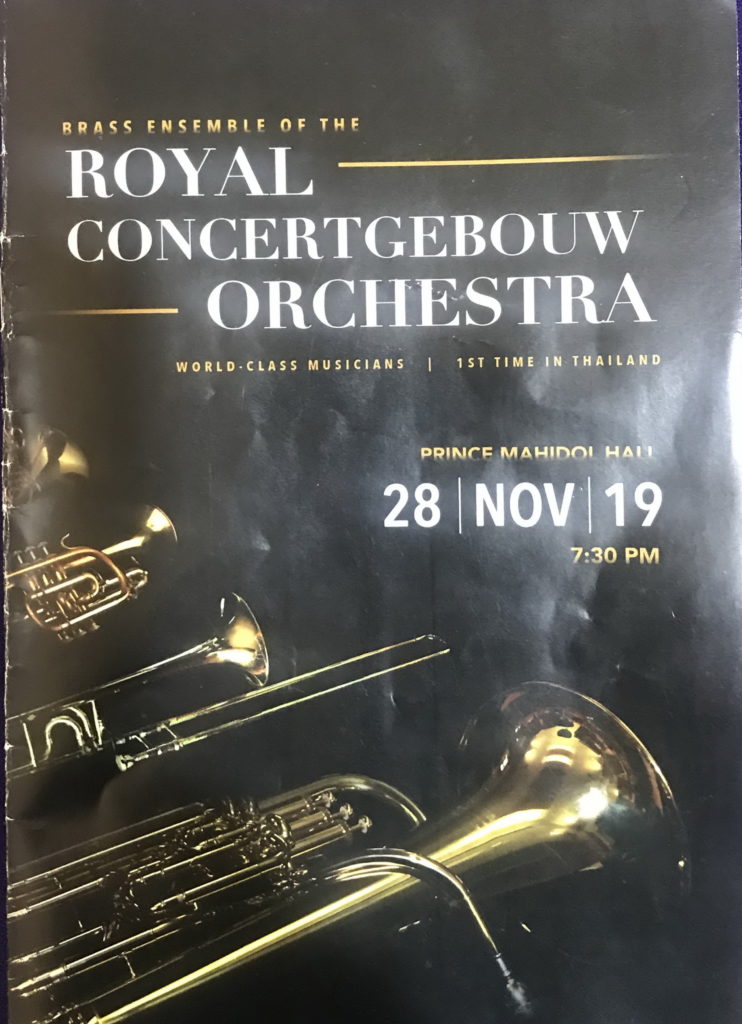

Europe’s “Top Brass” in Salaya

Chetana Nagavajara

Allow me to begin on a personal note. From 2008 to 2017, I was, once a year invited to the Free University Berlin as a Research Fellow, and I always timed my visit to coincide with the Berlin Music Festival in September, so that I could have the privilege of hearing the leading orchestras from Europe and America. 10 years were a period long enough to enable me to form an opinion, and I am prepared to confess that particularly 3 orchestras are held by me in high esteem, namely, the Concertgebouw of Amsterdam, the Philharmonia of London and the San Francisco Symphony. So when I heard that the Brass Ensemble of the Concertgebouw was coming to visit us, I made it a point not to miss it. Had I not been invited by the organizers, I would have bought myself a ticket. And I was not disappointed. A great orchestra is a sum of its parts, and to be able to hear the brass ensemble would already be good enough for me.

My experience with Berlin was not always a musical bliss. I felt uncomfortable with the resident orchestra of the Philharmonie Berlin. The musicians are virtuosos and are conscious of their virtuosity. They do not let the audience sense by themselves their musical superiority, but they physically exhibit their performing prowess. That virtuosity has to be seen too. That was why the visits by those distinguished non-German orchestras (including German orchestras of great merits, like the South West German Radio Orchestra from Baden-Baden which stupid politicians have decided to disband and merge into a lesser orchestra!) was a happy respite for a music lover – not an orchestra fanatic – like myself. I always admired the Concertgebouw for its musicality and its professionalism, the latter quality being extremely difficullt to explain, but I shall try. Every time I went to a concert by the Concertgebouw I could feel that they were never self-serving, but were intent on serving the music. Beyond that the musicians seemed to be enjoying themselves, and that enjoyment became contagious. The audience was drawn into that miraculous communal experience of music, imperceptibly and naturally. No exhibitionism was needed as an extra stimulus. It was more of a communication: it bordered on a communion, even. So I have since remained loyal to the Concertgebouw, and I went to Salaya last night to enjoy the concert as well as to express my gratitude for those happy hours in Berlin.

Contrary to what the Thai MC was saying about the plight of brass players in Thailand, I do maintain that they have not done too badly at all. I have been to the school big band contest almost every year and found the standard to be very high. Let us not forget that the number of school children learning brass instruments runs into hundreds of thousands. Let us not forget either those string players who are struggling very hard with very few qualified teachers. What these brass players need is the opportunity to hear “top brass” players, and they and their teachers were smart enough to throng to the Mahidol Sithakarn Auditorium last night to be enlightened. Many of us must have appreciated this rare occasion all the more for we have grown up with local, self-taught brass bands that usually constitute an indispensable part of a procession for the ordination ceremony of new Buddhist monks.

The concert programme was well thought-out. Those compositions chosen by the musicians themselves were varied, testifying to their ability to address a wide variety of styles, origins and historical periods. Added to their core repertoire was a new composition by our own Narongrit Dhamabutra and an arrangement for brass ensemble of two of Rama IX’s favourites by Vanich Potavanich. I shall deal with the top brass’s choices first. Even compositions by one and the same composer, in this case Johann Sebastian Bach, were interpretative challenges. The cantata, “Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme”, demands spiritual solemnity, whereas theBrandenburg Concerto No. 3 is full of worldly vitality. To place the two compositions in a sequence was a hard nut to crack, but the ensemble acquitted itself very well. What a remarkable feat in the change of styles, when they tackled, after Bach, those strange sounds and rhythms of Detlev Glanert’s Concertgeblaas! While admiring the power of adaptation on the part of the visitors from Amsterdam, we should not overlook their adroitness in dealing with old warhorses, like Giuseppe Verdi’s “Overture” to La Forza del Destino and Richard Wagner’s “Elsa’s Procession to the Cathedral” from Lohengrin. The former is unfortunately not a favourite of mine, and I cannot help feeling that the piece could not do justice to the great potential of this ensemble, while I found the Wagner excerpt more rewarding, the arrangement and the playing being so convincing that I could almost hear the sound of the timpani, (which was not there to start with!)

The second half of the concert proved to be even more challenging in terms of the range of styles and emotions. After the Festive Overture by Dimitri Shostakovich that gave the ensemble ample opportunity to demonstrate its virtuosity, the “Arrival of the Queen of Sheba” from the oratorio Solomon by Georg Friedrich Händel reinforced the impression that a really good brass ensemble could do just about everything that is normally the domain of other instruments, including the strings. Again came another leap in terms of styles: the Maria de Buenos Aires Suite by Astor Piazzolla was an admirable attempt to capture the spirit of a music growing out of a native soil, remote from Western Europe. (Although the composer himself had a solid training in classical music, what could really substitute for the inimitable charm of the bandoneon that he used so well?) If Piazzolla was also at home in jazz, which composer could ever rival George Gershwin in elevating jazz elements to the heights of classical music? The Concertgebouw Ensemble excelled in their Gershwin Selection, revisiting some of those familiar melodies with admirable freshness. Readers might chide me for being so liberal with my superlatives. But I am sure that my enthusiasm was shared by most members of the audience.

Last but not least, I shall address the two compositions that hail from the host country. The concert began with Narongrit Dhammabutra’s Suvarnabhumi Prelude, especially composed for the guests from Amsterdam. A rousing piece of music, into which local elements are seamlessly woven, is supported stylishly by Western instrumentation. If I could read the composer’s mind, I would say that he might have said to himself that he had waited for so long before a musical ensemble could produce for him the sound that he had been carrying inwardly for some time. I must say in all frankness that very few Thai ensembles have so far done full justice to Narongrit’s creations, sometimes for technical reasons, and sometimes for lack of adequate rehearsal. The concert concluded with H. M. Medley, an arrangement for brass ensemble of Rama IX’s compositions by Vanich Potavanich, himself a distinguished trumpet player. It was a fitting conclusion to an evening of musical bliss.

I have been describing up to now what I heard in the evening of November 28, but this review would be incomplete without an account of what I saw on the stage. After each item, the 11 musicians would shift their (standing) positions, taking turns to lead the ensemble and picking up different instruments (either of the same or of different category). This they did with such amazing ease that made me wonder why they did not get mixed up at all. Those shifts and changes in styles that I referred to earlier were so well matchedphysically by the movements on stage of these ladies (sorry, there was only one lady among them, a British French horn player) and gentlemen from the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra. How lucky we were to be able to hearand see their performance!

My final congratulations must go to the organizers of the concert. The mammoth Mahidol Sithakarn Auditorium, located 18 kilometers away from Bangkok in Salaya, was almost full. Among the audience were young music students, including those from military music schools, to which we should express our gratitude for the rebirth of classical music in Thailand in the 1960s. Hopefully these able organizers would, on future occasions, lend a helping hand to local musical ensembles that are doing their best in terms of performance, but lack managerial skills to attract audiences. Let us face it: we are getting better and better on the performing front, but the public can only be attracted by way of PR stunts. A traditionally musical nation is going tone-deaf. It should not be.