MAN RISES WHEN THE DINOSAUR APPEARS : 18 MONKEYS DANCE THEATRE’S “PARTY ANIMAL”

MAN RISES WHEN THE DINOSAUR APPEARS : 18 MONKEYS DANCE THEATRE’S

“PARTY ANIMAL”

Chetana Nagavajara

There is no more need to talk about the virtuosity of Jitti Chompee and his dance troupe. You don’t have to be an expert in contemporary dance to appreciate that. What has always intrigued me is how this pioneering group of dancers has used its technical prowess to convey a succinct social and philosophical message, and let’s face it, the message is becoming more and more enigmatic.

Had I been a specialist in contemporary dance, I would have had to anchor the performance on 19 November 2018 at the Neilson Hays Library in a web of cross-associations between various art forms; in other words, I could have written a case study of the “Mutual Illumination of the Arts in the 21st Century”. The choreographer admits that he has been inspired by sculpture (and he is not the only one to fall under the spell of this particular art form, for innumerable architects compensate for their being “failed sculptors” by way of edifices that look very interesting, but are, alas, almost inhabitable!) We have information that Jitti has been impressed by the sculptures of the ageing Louise Bourgeois, whose feminist subversiveness does leave a stamp on “Party Animal”. And what about Berlinda de Bruyekere’s anti-war critique? She was present too in spirit. And we should not forget the “techno” music from the Berghain Nightclub in Berlin, which is supposed to be unique, while the club itself remains a libertine sanctuary not easily accessible to the public.

Sometimes knowing too much about the background of an enterprise becomes distracting. I was not prepared to be distracted in that way, and did allow the performance that I saw (and heard) at the Neilson Hays Library to speak to me directly. And it did speak to me in several significant ways.

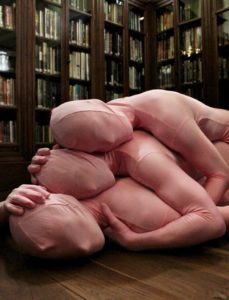

My first reaction was that this show is an affirmation of the potential of the human body, even a celebration thereof. Those dancers clad in one-piece tight and transparent fabric in pink from head to toe could do so much with their bodies. Those of us who had seen previous productions by “The 18 Monkeys Dance Theatre” would not fail to notice that there were postures and movements that we had not seen before. The agility of the body movements was staggering. In the first part of the performance, the 3 lead dancers were dancing on all fours, thus reflecting the title of the performance, “Party Animal”. They could do so much without standing upright. I cannot resist the temptation of calling this a posture of the “Homo non-erectus”, but on further reflection and in order to avoid any lewd interpretation, shall have to switch to “Homo pre-erectus”, that is to say, human beings at the stage before becoming “Homo erectus”. Man is still close to animals and enjoys the freedom of movements that we normally associate with animals. The dancers intermittently uttered sounds that were incomprehensible, more akin to those of animals.

Then came a turning point : they began to sing a “folk song” in German, composed during the early years of the Nazi rule, and still sung in the German armed forces today, beginning with, “It’s so nice to be a soldier…”. The message is quite subtle: the beginnings of the human language that expresses merriment are already contaminated by a belligerence of sorts – a warning that might escape many people. But in the context of this show, the glee derived from being a soldier may be an instinct that accompanies human beings still in their bestial stage of evolution, a devastating proposition coming from a seemingly harmless dance performance!

But the real turning point came with the appearance of the dinosaur, so short it may have been, but it brought with it a significant change. The men shed off their pink suits and donned casual dresses, then started to dance to “techno” music while standing up, thus representing the Homo erectus. This was the acme of the contemporary, for the music hailed from that inimitable and exclusive Berghain Nightclub of Berlin that is so difficult to get in and in which absolute freedom is accorded to those 1500 lucky people who are allowed entry. I am afraid I don’t understand the message here, being unfamiliar with the (sub)culture of that “holy” place, in spite of being a regular visitor to Berlin. This second part of the show was distinguished in terms of choreographic skills, but having experienced Merce Cunningham and the kind of revolutionary music that he used, I found that the “techno” version from Berlin did not quite match the complexity and sophistication of the choreography. But the main point here has to do with the dance and how it conveys deeper meanings. If the dinosaur announces the coming of the Homo erectus, this is something we must ponder over. So man rises when the dinosaur appears. Have we moved beyond our ancestors, both in the human and the animal domains?

The third and last part of the show made room for the entire corps de ballet or the full company, including 16 student trainees, clad again in transparent pink suits. They had been well trained as dancers, although the choreography here was not as demanding as that for the lead dancers. They filled the original reading space of the Neilson Hays Library, and were not there just to be seen, but to interact with the audience as well. They appeared to be hungry, and when the choreographer threw leaves of cabbage to them, they acted like a herd of rabbits. Why cabbage in the final scene of this impressive spectacle? I would venture to say that these novices are meant to be herbivorous. In this sense, the show ended on an optimistic note that the new generation of human beings would cease to be harmful to other living beings. After all, most dinosaurs were herbivorous, and only human beings in the intervening period between the appearance of the dinosaurs and the Homo erectus were carnivorous. A Buddhist cannot help deciphering an even deeper meaning from “Party Animal”: all living-beings are “beings of this world” (satta-loka) and have equal rights to exist. What remains a mere wish in the real world becomes a statement of fact in art. A French poet once said : “Qu’ importe, que le rêve mente, s’il est beau?” (It does not matter that dreams lie, if they are beautiful.) And this dance performance is undeniably a thing of beauty.

After the performance had ended, members of the audience lingered on for quite a while, taking photographs of the pink dancers who were lurking in all corners and niches of the library, as if to say that we are all-pervasive and you can’t get rid of us so easily. I am sure “Party Animal” must have left an indelible memory on many among the audience on account of its inspiring artistry and, last but not least, intellectual/hermeneutical challenge.

Having seen most of Jitti’s creative works these past few years, I am beginning to wonder as to how we can persuade the world of Thai classical dance to espouse innovative choreography. After all, there must have been primeval “choreographers” who gave birth to the dance, and that need not have been be an Indic god! The race between human beings and dinosaurs should begin now.